Bringing Peatlands Back to Life: A Climate Project at Lækur Farm in W-Iceland

Uncover how draining peatlands impacts climate change and how the Rewet project at Lækur Farm is measuring carbon to inform restoration strategies.

Why Peatlands Matter

Peatlands are known around the world as powerful natural carbon stores. When they stay wet, they can lock away carbon for thousands of years. But once they’re drained, that balance changes. The peat begins to break down, and large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO₂) are released into the atmosphere.

In Iceland, drained peatlands are believed to contribute a significant share of the country’s CO₂ emissions—possibly even more than all other sectors combined, not counting land use. While this makes peatlands a clear climate concern, there’s still a lot we don’t know. We need better data to understand exactly how much carbon is being released—and which restoration strategies will be most effective in reducing those emissions.

A Closer Look at Lækur Farm

Lækur Farm is a quiet, grassy field in western Iceland. It covers 11 hectares and was drained in 1961—part of a country-wide effort to create more farmland. But this land was never actually used for farming or fertilized. Instead, it became a wild grassland sitting on top of a deep layer of peat—over 2 meters thick in some places. That makes it a perfect place to study what happens to carbon after peatlands are drained.

How We’re Measuring Carbon

To find out whether the land is releasing or storing carbon, we’ve set up an eddy covariance tower in the middle of the field. This tall, high-tech system works a bit like a weather station, but instead of just wind and rain, it measures how much CO₂ moves between the land and the atmosphere—in real time, every half hour. This gives us a detailed picture of the land’s carbon balance across seasons and weather conditions.

What’s Next: Rewetting the Land—and Scaling Up

Soon, the land at Lækur Farm will be rewetted—ditches will be blocked, and water levels will rise to restore natural peatland conditions. This offers a unique chance to measure how CO₂ emissions respond to rewetting, comparing data collected before and after restoration. Will emissions go down? Can the land return to being a carbon sink?

But the project doesn't stop there.

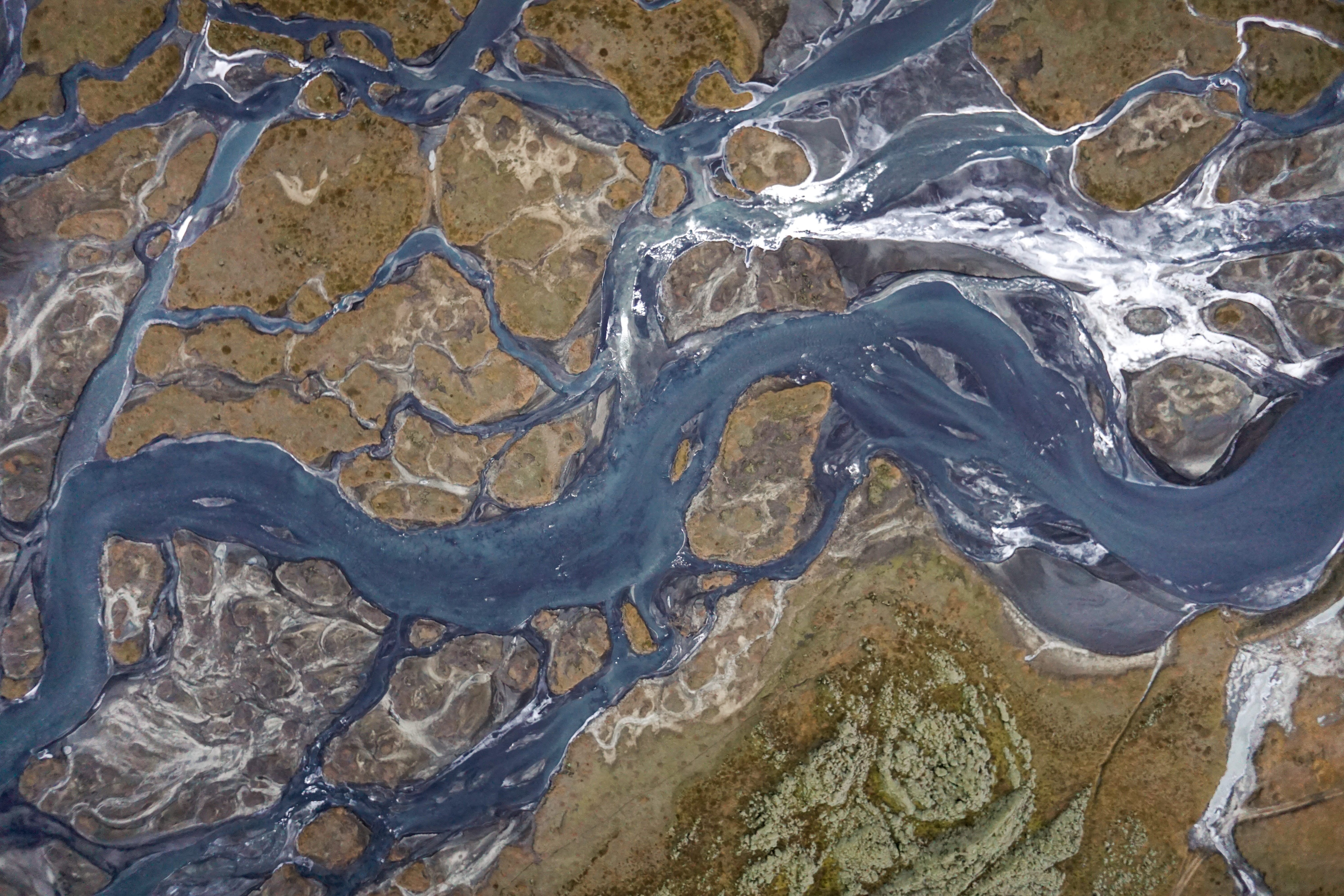

The research team also aims to scale up these insights beyond a single location. By combining field measurements from the eddy covariance tower with drone-based and satellite remote sensing data, the goal is to map and model carbon fluxes across other drained peatlands in Iceland. This approach could help identify high-emission areas and prioritize them for future restoration efforts.

Since 2023, Svarmi ehf. responsible for the remote sensing data collection and analysis in this project, has been regularly collecting data during both the growing and non-growing seasons. This robust dataset provides a strong foundation to extend the findings to similar ecosystems and supports efforts to estimate the total carbon emissions from Icelandic peatlands on a broader scale.

Why It Matters

Peatlands might seem quiet and unremarkable, but they hold a powerful role in our climate system. This project is about more than just one field—it’s about understanding how Iceland’s landscapes contribute to or help solve the climate crisis. By tracking what happens at Lækur Farm, we can:

- Improve carbon estimates in Iceland’s climate reporting

- Inform better land management and restoration efforts

- Show the real impact of rewetting peatlands

With more accurate data and practical action, peatlands like this can move from being part of the problem to becoming part of the solution.

Similar articles

Svarmi welcomes James d’Ath from the TNFD to Iceland for Nature Day

What does the EU Nature Restoration Law mean?